Many people in the United States use the term “Scotch-Irish” instead of “Scots-Irish.” In this paper, the term “Scots-Irish” is used because it tends to be more universally accepted. Many people in other parts of the world have pointed out that Scotch is a beverage while Scots is a nationality.

Submitted by Drew Barnhart, our summer intern. This is a summary of her research paper of the same title.

[divider]

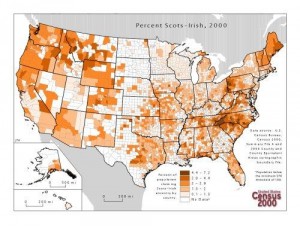

The Invisible Scots

Too often, communities fail to recognize what is right under their noses. They are able to celebrate the modern ethnic diversity of their area, but sometimes forget the ways that the original settlers of the land have shaped the people and customs of the area. These early pioneers molded not only their descendants’ mentalities but also others who would seek to live among them. Perhaps one of the most under recognized demographics is the Scots-Irish because they were often the first to enter the areas they settled, so they were not worried about defining themselves as an ethnic group. Despite their lack of recognition, historical personality traits demonstrated by the Scots-Irish are still evident in their descendants.

Too often, communities fail to recognize what is right under their noses. They are able to celebrate the modern ethnic diversity of their area, but sometimes forget the ways that the original settlers of the land have shaped the people and customs of the area. These early pioneers molded not only their descendants’ mentalities but also others who would seek to live among them. Perhaps one of the most under recognized demographics is the Scots-Irish because they were often the first to enter the areas they settled, so they were not worried about defining themselves as an ethnic group. Despite their lack of recognition, historical personality traits demonstrated by the Scots-Irish are still evident in their descendants.

The History of Scots-Irish People

The history of the Scots-Irish people is riddled with hardship and violence. Their difficult history originates in their native country of Scotland. The land’s harsh topography and climate made it challenging to cultivate crops and even more difficult for a central government to control its people. This led to many separate clans who often fought each other for resources and survival. In addition to violence between clans, Scotland was often attacked by the English.

During the 1600s, about 200,000 Scots from the lowland areas moved to Northern Ireland, especially Ulster and Donegal.

Loyalty

One trait that has stood the test of time is a strong sense of loyalty, especially to family and to their country. It is speculated that this attribute is rooted deep in the Scots-Irish’s Celtic ancestry, but it was strengthened by the constant fighting between clans. Scots learned that through loyalty, they could hold out against an enemy. This became especially true when the Scots were attacked by an outsider. James Webb, who served as Assistant Secretary of Defense and Secretary of Navy during Ronald Reagan’s administration, observes that “the hardships of this existence, plus the frequent attacks by organized English armies designed to break their spirit, bred a peculiar form of nationalism among the lowland Scots.” This sense of loyalty also aided them in Ireland when they were attacked by both the English and the Irish. Through these attacks, they came to learn that they could rely on each other. Loyalty stuck with the Scots-Irish as they settled in America because, they had to rely on each other to survive on the frontier.

Today, this sense of loyalty is manifested in different ways. Many communities originally settled by the Scots-Irish relate to this “Celtic tie of kinship,” and tend to be very supportive of military troops. Often young men and women of these communities join the military themselves. Family pride and loyalty is also very common in these communities. Many families of Scots-Irish decent can trace their families back hundreds of years. The number of Scottish Festivals in Scots-Irish areas also attests to the loyalty the Scots-Irish feel to their distant relatives across the sea.

Distrust of Higher Authority

Despite being incredibly loyal and even patriotic, the Scots-Irish tend to have an extreme distrust of high authority. Perhaps due to Scotland’s own turbulent central government during the time of the Scots-Irish exodus, they tended to be loyal to local leaders rather than a king or national government. One example of this is the lack of loyalty to the Catholic Church in Scotland even before the Protestant reformation. The English furthered this conviction by strongly discouraging the Scots’ Presbyterian faith in Ireland, encouraging them to go to America to seek religious freedom.

These events set the tone for the Scots-Irish settlers’ attitudes in the New World. Often, these hardy men and women were just as likely to attack meddlesome Quakers and Germans of Pennsylvania as they were to war with the Native Americans.

Willingness to Fight

Closely paralleling the trait of rebelliousness towards higher authority is the Scots-Irish readiness to fight. Highlighting this trait, is Sir Walter Scott’s statement “I am a Scotsman; therefore I had to fight my way into the world”. Like many other traits, this aggressive nature can be traced through their history. After many years of struggling against the English, the Scots earned the reputation of being extremely tough and skilled at combat. When England and Scotland were united under King James I, the English decided to encourage the Scots to move to Ireland in order to create a “Protestant plantation” that would reduce the likelihood Irish attacks. This strategy worked so well for the English that many American settlers wanted the Scots-Irish to move to their colonies and act as a buffer between the civilized regions and the wild Native Americans. When the Scots-Irish moved to America, they certainly fulfilled that expectation. However, they also tended to attack other European settlers, sometimes causing the people who encouraged their immigration more harm than good. Thus, they tended to make violent neighbors wherever they settled.

The trait of aggressiveness also came in handy during the Revolutionary War. The book How the Scots Invented the Modern World by Arthur Herman attests to this. Herman states that although it is questionable how many colonists actually owned or could even use a gun, there is no doubt that the Scots-Irish from the frontier were more than able to fight using firearms. According to Herman, they formed the “backbone of George Washington’s Continental Army.” With this history, it is not surprising that many young men and women from Scots-Irish ancestry join the military, and continue to hunt wildlife. Many people of Scots-Irish ancestry tend to align themselves with Republican rhetoric, including the right to bear arms. This belief in owning weapons for self-protection links directly to the Scots-Irish willingness to fight.

Individualism and Self-Sustainability

Perhaps the most intriguing of the traits associated with the Scots-Irish is their individualism and self-sustainability. Cornelius Weygandt, a former professor at the University of Pennsylvania and Scots-Irish descendant, describes the Scots-Irish individualism as “an untamed love of loneliness” and “a hunger for wild nature” that is most likely a remnant of their ancestors, the Highland Gaels. If these traits were not already part of their ancestral culture, they certainly acquired it early on from their fight to survive in the harsh environment of Scotland. However, it is not until their move to America that the impressiveness of this trait can be fully recognized. Their individualism allowed them to settle far away from established society. By 1790, over 60,000 Scots-Irish had entrenched themselves in the most perilous area of Pennsylvania, the area west of the Allegheny Ridge. It is also speculated that this individualism was the basis of the mindset common among pioneers who would later explore the American West.

Self-sustainability and individualism manifest themselves in many ways in the decedents of the Scots-Irish today. Some examples are being frugal, killing or hunting animals for food, growing vegetable gardens, and building houses and furniture for their own use. Claire Myers, an elderly woman of Scots-Irish descent remembers her childhood when her family “did not rely on anyone else to put food on the table.” To many people this would mean working for money in order to buy food, but Mrs. Myers specifies that her family did not need a grocery store to provide them with sustenance. Her family grew and canned their own vegetables and fruits, and owned a small flock of chickens to provide eggs and meat.

Although it may not be immediately apparent, most people exhibit traits they have acquired through the journeys of their ancestors. The traits of loyalty, family pride, eagerness to fight, and self-sustainability are enduring traits that can be applied to the today’s descendants of the Scots-Irish settlers. They are the men and women in rural areas, the soldiers, the hunters, the conservatives, the frugal, and the self-sustaining. Although many may not recognize the source of some of their distinctive traits, these qualities have molded the regions settled by the Scots-Irish and those who live there. They have also shaped the regions in Ireland and Scotland where they originated.

Arthur Herman, former professor of history at George Mason University and Georgetown University states

…being Scottish is more than just a matter of nationality or place of origin or clan or even culture. It is also a state of mind, a way of viewing the world and our place in it… [It is] so deeply rooted in the assumptions and institutions that govern our lives today that we often miss its significance, not to mention its origin.

Hopefully, common people will begin to identify more fully the importance of their past and the history of the nationalities that have shaped their land. Only when this happens, will the Scots-Irish gain the recognition they deserve.

[divider]

Too often, communities fail to recognize what is right under their noses. They are able to celebrate the modern ethnic diversity of their area, but sometimes forget the ways that the original settlers of the land have shaped the people and customs of the area. These early pioneers molded not only their descendants’ mentalities but also others who would seek to live among them. Perhaps one of the most under recognized demographics is the Scots-Irish because they were often the first to enter the areas they settled, so they were not worried about defining themselves as an ethnic group. Despite their lack of recognition, historical personality traits demonstrated by the Scots-Irish are still evident in their descendants.

Too often, communities fail to recognize what is right under their noses. They are able to celebrate the modern ethnic diversity of their area, but sometimes forget the ways that the original settlers of the land have shaped the people and customs of the area. These early pioneers molded not only their descendants’ mentalities but also others who would seek to live among them. Perhaps one of the most under recognized demographics is the Scots-Irish because they were often the first to enter the areas they settled, so they were not worried about defining themselves as an ethnic group. Despite their lack of recognition, historical personality traits demonstrated by the Scots-Irish are still evident in their descendants.